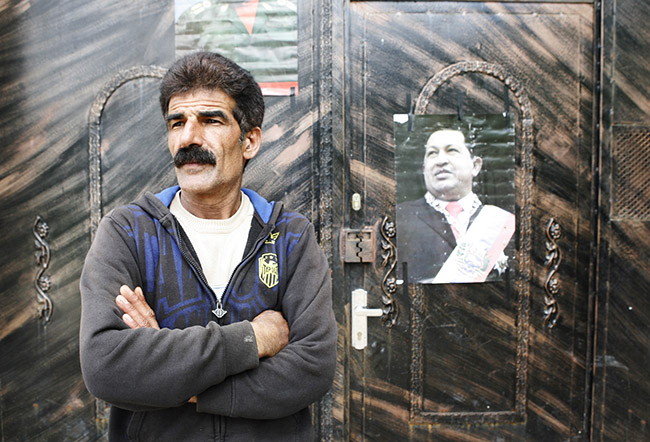

On this occasion I met Khaled Daraghmeh of Khan al Lubban to talk settler violence, sovereignty over land and resistance. The full story was first published on AJE.

All images © silviaboarini.com

Khan al-Lubban, occupied West Bank – “Everything can be protected,” Khaled Daraghmeh told Al Jazeera as he sat on the porch of Khan al-Lubban, or “caravanserai of the frankincense”, a now-decrepit structure that his family has owned for generations and Israeli settlers have attempted to seize for the past 17 years.

“We can smoke Palestinian tobacco instead of Marlboro. We can eat the zatar from our gardens. We can work and invest in our land. We have to stay strong,” he said.

The Khan is in occupied Palestinian territory in the Nablus governorate and in Area C, the 60 percent of the West Bank under full Israeli administrative and military control. Today, the Khan is surrounded by four illegal Jewish colonies: Maale Levona, Eli, Eli B and Shilo, and it is the only sizeable obstacle to their territorial contiguity. In the fight for the legitimacy of sovereignty over land, it is a hotly disputed site. A year ago, the right-wing settler organisation Regavim petitioned the Israeli Supreme Court to see the Khan classified as a public space and transferred to Israeli control.

According to Ari Briggs, director of international relations at Regavim, past uses of the Khan as a resting place for travellers along the incense route and later as a police station, indicate that “the Khan has always been a public building. It can’t just be stolen by criminal people”. But in an unexpected ruling late last year, the Israeli Supreme Court recognised the area as Palestinian private property and Daraghmeh as its legal owner.

“This victory surprised me a bit,” Sami Ersheid, Daraghmeh’s lawyer, told Al Jazeera. “It was a difficult case and the settlers have the support of the army.” In this case, though, the military did not seek control of the area for security reasons, so the issue centred on planning rights.

“This is a very sensitive area and settlers have employed very ambitious means to try and control it,” Ersheid added. “It is a small victory, but an important one.”

Still, in the context of ongoing settlement expansion, Daraghmeh is all too aware that the future of the Khan is not yet secured. According to the Israeli human rights group Yesh Din, there is little protection for Palestinians in Area C. “Jewish settlers are able to use harassment, religious claims, legal recourse and archaeology as tools of dispossession with impunity,” spokesperson Reut Mor said.

Born three months before the Six-Day war of 1967, the only life Daraghmeh knows is life under occupation. At 47, he is clearly proud to still be on the land. “My family and I have been attacked so many times, harassed so many times that I don’t count any more,” he said.

Busloads of settlers began arriving at the Khan some 15 years ago. “They claim that Moses bathed in the Khan’s spring and so the place has religious significance for them,” Daraghmeh said.

The international organisation Premiere Urgence – Aide Medicale International monitors settlers’ violence in the area. Aside from forced entry into Daraghmeh’s property, settlers also regularly move onto the roof of the Khan in order to throw objects at the family and into the garden. They have contaminated the Khan’s well, poisoned Daraghmeh’s cow, killed his horse and burned his tractor, the group reported.

In mid-April, Daraghmeh was arrested after preventing settlers from accessing his property. He estimates that he has been detained at least 17 times in his life. “Israel accuses me of beating the settlers and yet they are free to use violence to enter my house. Do you think it’s normal?” he asked.

“I have a comfortable home in Lubban as-Sharqiya,” Daraghmeh added, pointing to the nearby village. “But if I leave the Khan they will take it. I have to stay here with my family to guard it. I can’t work. I have no money to provide for my wife and children as I should.”

The Supreme Court ruling stated that the fences he put up around the property to protect his family from attacks need not be removed, as Regavim had requested. But the ruling offers little else in terms of protection. “It is still unlikely that settlers will be prosecuted if attacks continue,” Ersheid said.

Regarding past violent incidents at the Khan, Daniel Israeli, the head of the Israeli police unit coordinating with Palestinian police in the Benyamin Council, told Al Jazeera: “There have been complaints about attacks on both sides and we investigate all attacks.”

Figures made public in 2013 by Israeli human rights NGO Yesh Din about Israeli police investigations into settler violence revealed that of the nearly 900 attacks against Palestinians reported to the Israeli police between 2005 and 2013, only 8.5 percent resulted in indictments, while 84 percent of files were closed “due to police investigation failures”.

“No Israeli institution sees it as its duty to protect Palestinians in Area C,” Mor said, noting even a ruling issued by the courts of the occupying power does not always guarantee results. “In the absence of law enforcement, Palestinians remain unprotected.”

Prior to the Supreme Court’s ruling, the Civil Administration, the army body administrating civilian affairs in the West Bank, declared the Khan an antiquity site, thus reserving the right to approve archaeological excavations there.

“The Supreme Court did not overturn this classification, so our next step is to have it removed,” Ersheid said.

An archaeological dig already took place at the Khan in 2013 and sought, Daraghmeh maintains, to substantiate settlers’ religious claims.

The Civil Administration spokesperson’s unit was unable to comment on this but told Al Jazeera in an email that according to the Interim Agreement on the West Bank and the Gaza Strip of 1995, “Israel is exclusively authorised to conduct or authorise any excavations in Area C”.

Hamdan Taha, deputy minister at the Palestinian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, disputed this claim. “Archaeology and cultural heritage are used by Israel as an ideological instrument,” he told Al Jazeera. “The Khan is in occupied Palestinian territory and protected by international law.”

Yonathan Mizrachi of Emek Shavek, an Israeli NGO seeking to de-politicise archaeology, also believes Palestinians should be in charge of heritage on their land. “It is unclear what settlers base their claims on, or what the digs were trying to prove,” he told Al Jazeera. “It was only to get rid of the family living there.

“Even if the site had been Jewish, so what?” he added. “There are many Muslim sites in Israel. What are we going to do?”

Despite an official piece of paper proving what he already knew, Daraghmeh remains a prisoner in his own home.

“No one can protect me, but [it is] my duty to remain,” he told Al Jazeera. “The fact that our house is targeted by the occupation is what forces me to stay. If it wasn’t, I would live freely.”

He added: “If this was the last thing they take, I would give it to them. But do you think it would be?

“No,” he said. “If they take the Khan, they will take everything – including my children’s future.”